Simple, complicated and complex

Types of environment that should change how we think

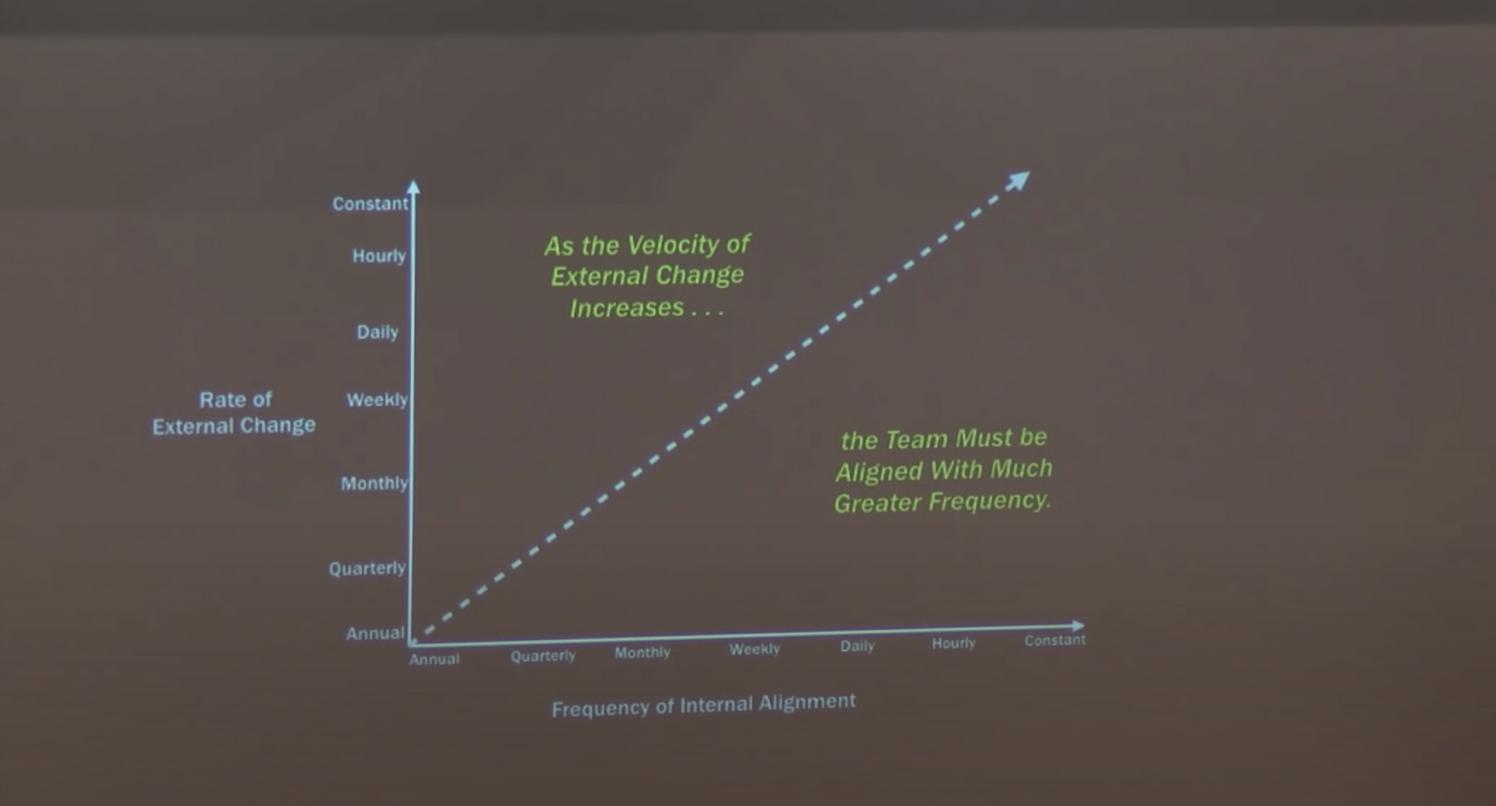

I feel this slide by Gen. Stanley McChrystal (who led counter-insurgency special forces in the Iraq war and wrote the book “Team of Teams”) is crucial in understanding why the type of environment should affect our behaviour. It tells us that what’s most important is to ensure decision making frequency is aligned with the rate of external change. This is insightful because McChrystal isn’t talking about output here - making sure supply meets demand - he’s specifically saying that, right or wrong, you need to match or exceed the decision making cadence of your environment.

We can describe the areas on the diagram from left to right as simple, complicated and complex environments (or systems) respectively. On the bottom left we have simple systems:

Simple systems have a low rate of change because they are highly predictable. Typically they are formed of one or more processes that turn inputs into outputs. For example when you pull the chain on a toilet, the toilet flushes. There are simple rules explaining when the flush will work and what it does. Nearly everyone has a good internal model of how to operate a toilet, and no matter how many different toilets you operate you will (probably) not suffer any mental fatigue purely by flushing.

Complicated systems are a large set of simple systems, usually joined together through conditionals like “if the brake is pressed the brake light should be on, otherwise it should be off”. Complicated systems can be best thought of as a flow chart that you can follow to see how everything works. Computers and most pieces of technology fall into this category, though their flow charts may be large.

In all complicated systems it’s possible to understand how something works by zooming in on a specific subsystem (like a computer’s mouse). In doing this we’re automatically filtering out all the information we know will be irrelevant (like how the keyboard works). You can continue to “zoom in”, breaking down the process further and further until you reach the part of interest. For example zooming from the mouse, to the buttons on the mouse, to how the switch under the left clicker is connected. It can be hard to keep up with complicated systems if people are constantly tweaking or making small changes to them, but it’s never impossible to do.

Complex systems introduce the problem of perspective. Complex systems are where complicated systems become non deterministic, or at least we cannot know all of the inputs. The stock market is a complex system; it depends not only on what you do, but also what other people do - something which we cannot know in advance. There cannot be a great flow chart for the stock market because we can’t exactly tell what the effect of certain changes will be. We make predictions but we can never be sure.

In such a complex environment we struggle to measure the success of our own behaviours. A bad stock market investment today always has the potential of becoming a good investment tomorrow. Errors in judgement are not avoidable in complex systems because the information needed to make the right decision is not always available (to anyone). Because of this it’s hard to know what “efficiency” looks like too. The adage “50% of advertising spend is wasted: we just don’t know which 50%” exemplifies the problem. When it’s hard to know how you’re doing and what’s working, it’s very hard to optimise for that.

Gen. Stanley McChrystal is showing us how to play in a complex system with his slide. It’s through making increasingly rapid decisions, even without complete information. You can’t alter the environment, but you can control the behaviour of a part of it - yourself. In complex games with other players it’s also advantageous to increase the complexity of a situation deliberately by making lots of behaviour changes, saturating your opponent’s decision making throughput. We see examples of this in the idea of both market disruption (like uber displacing local taxis) and more traditionally a military doctrine called manoeuvre warfare (as practised in the opening stages of the Iraq war).

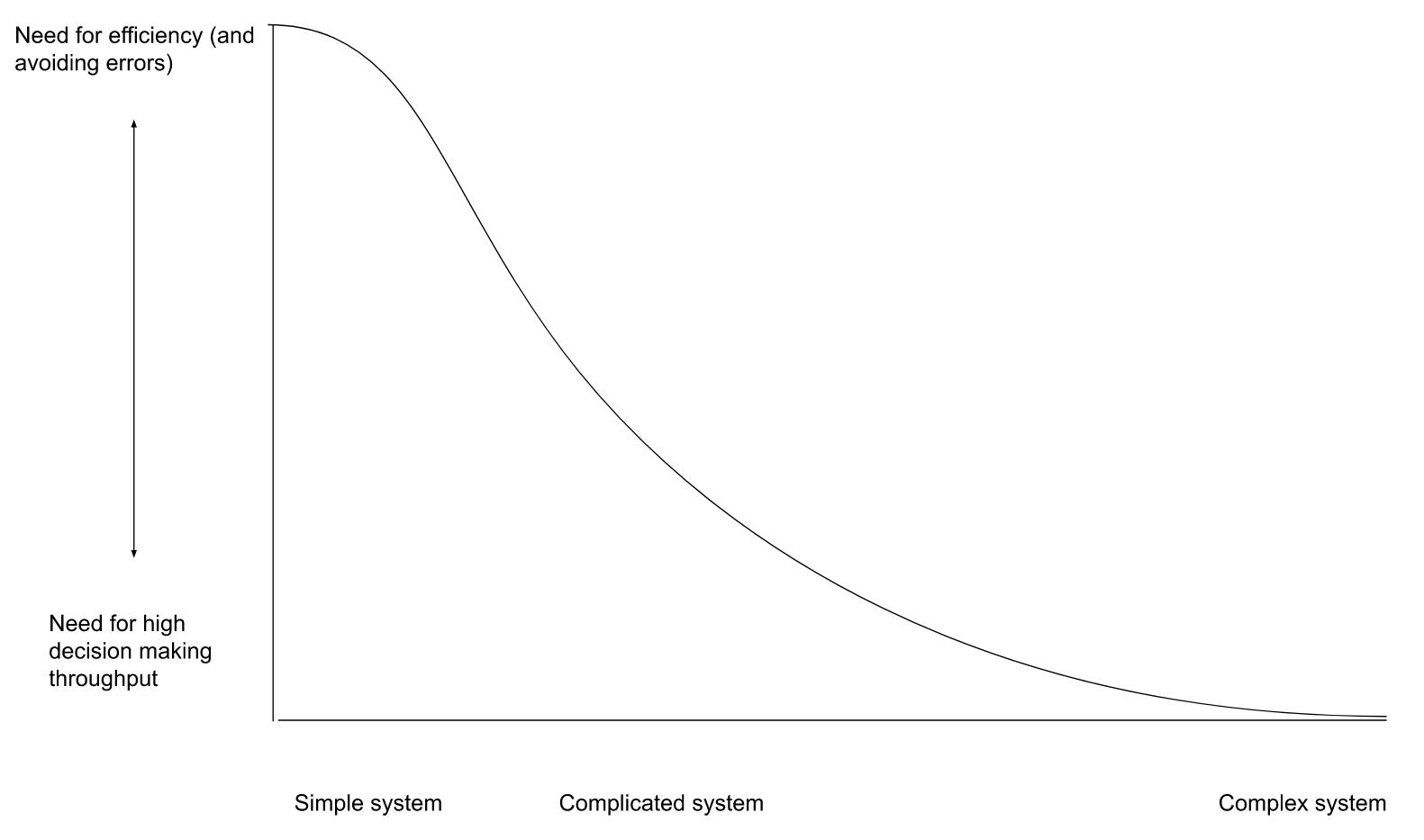

Efficiency typically means taking less decisions rather than more because each decision is a possible inefficiency. This creates an interesting problem - trying to be efficient in a complex system leads to fragility and paralysis. This is a common problem as our current managerial/leadership culture is strongly rooted in manufacturing and more specifically scientific management.

The systems we have today that need efficiency and to avoid errors tend to be simple or complicated. We need to repeat them often, they have to be that way. Factories make many instances of the same car and that’s something you want to be predictable. As technology progresses, predictable problems are and will continue to be increasingly solved by automation. This leaves the complex realm to people, not machines. That seems to mean that we’re going to need to start forgetting about errors and efficiency outside of the machines we design, and instead start worrying about decision throughput and how quickly we can evolve to thrive in rapidly changing situations.

Relevant books/resources:

- Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World (General Stanley McChrystal)

- Turn the Ship Around!: A True Story of Building Leaders by Breaking the Rules (L. David Marquet)

- Finite and Infinite Games: A Vision of Life As Play and Possibility (James Carse)

- Overview of manoeuvre warfare | Summary of UK defence doctrine